The right to have access to public services (in EU terminology ’services of general interests’, SGIs and ‘services of general economic interests’, SGEIs) is of crucial importance for citizen. It has also been confirmed by the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union. This right involves the requirement for establishing an effective consumer protection regime both at the national and the EU level. Due to the evolution of the legal framework, the EU is an important supranational actor in the regulation of public services today. The paper analyses the evolution of consumer protection in this field from the very beginning stage of the European integration until today, with a special focus on secondary legislation of the European Union aiming at liberalization in the energy sector. Read more… (Ildikó Bartha)

The right to have access to public services (in EU terminology ’services of general interests’, SGIs and ‘services of general economic interests’, SGEIs) is of crucial importance for citizen. It has also been confirmed by the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union. This right involves the requirement for establishing an effective consumer protection regime both at the national and the EU level. Due to the evolution of the legal framework, the EU is an important supranational actor in the regulation of public services today. The paper analyses the evolution of consumer protection in this field from the very beginning stage of the European integration until today, with a special focus on secondary legislation of the European Union aiming at liberalization in the energy sector. Read more… (Ildikó Bartha)

Introduction[*]

The right to have access to public services (in EU terminology ’services of general interests’, SGIs and ‘services of general economic interests’, SGEIs) is of crucial importance for citizen. It has also been confirmed by the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union.[i] This right involves the requirement for establishing an effective consumer protection regime both at the national and the EU level.

Due to the evolution of the legal framework, the EU is an important supranational actor in the regulation of public services today. The paper analyses the evolution of consumer protection in this field from the very beginning stage of the European integration until today, with a special focus on secondary legislation of the European Union aiming at liberalization in the energy sector. In doing so, our analysis focuses on the content of universal services, the scope of social protection granted to consumers with special needs, as well as the ‘market-based’ consumer rights in the selected regulatory areas. In this context, we also examine the role and degree of discretionary powers left to national authorities in defining the underlying concepts and ‘appropriate’ measures needed to take to protect the interests of consumers. Finally, we examine on the basis of some examples from the electricity and gas sectors, whether the relevant European and national rules are able to grant a real safeguard for consumer interests in any case.

1 The concept of the consumer and services of general interests

In EU consumer law documents[ii] the ‘consumer’ is generally defined as a private, human person who purchases goods or services for purposes outside their trade, business or profession. Therefore, at the very beginning stage of the European integration, the ‘consumer’ has fallen outside the realm of SGI regulation, since these sectors (telecommunications, railways, postal services, electricity and gas) were traditionally operated under the ownership, control or strong oversight of the state and public bodies (Johnston, 2016: 93). It means that there was a quite clear distinction between ‘citizens’ as recipients of public services and consumers as equivalent category in other sectors operating under normal market rules. Such a distinction is a logical consequence of the fact that, before the adoption of the Single European Act (SEA) of 1986, the matter of public service provision was not at the heart of the European integration process. In line with the principle of subsidiarity under Article 5 of the Treaty of European Union (hereinafter TEU), a consensus has been reached between the Member States that each country has the competence to organize and finance its basic public services (Bauby, 2014, 99). The “Europeanization of public services”[iii] started only in the mid-eighties with the entry into force of the Single European Act. The SEA, together with the Commission’s white paper on reforming the common market, set the objective of the creation of a single market by 31 December 1992. As the national markets in transport and energy have become integrated with this conception, public service obligations have been obstacles to market creation (Opinion of AG Colomer in case C-265/08 Federutility;[iv] Prosser 2005, 121).

2 Consumer protection in the energy sector

The process of liberalization of energy services started in the mid-nighties. While the liberalization was extensive, for instance, in electronic communications, the energy market remained dominated by the presence of natural monopolies, where the specific public service grounds (universal service obligation, security of supply, environmental concerns) gave the Member States more opportunities to derogate from market liberalization (Prosser 2005, 174 and 192–194; Hancher and Larouche, 2011).

Measures for liberalization were adopted both in the electricity and the gas sectors. Consumer rights have gradually been extended in subsequent „energy packages”, i. e. in the amendments of the first electricity and gas directives. The first directives permitted Member States to impose on undertaking operating in the electricity/gas sector public service obligations „which may relate to security, including security of supply, regularity, quality and price of supplies and environmental protection, including energy efficiency, energy from renewable sources and climate protection.”[v] As we can see, public service obligations formulated this way are wideranging and universality of service provision is not the key to these PSOs (Sauter, 2014, 199). The second electricity directive already contained a separate provision on universal services, an identical clause, however, was missing from the second and also from the third gas directive. The USO provision remained essentially unchanged in the (currently applicable) third electricity directive obliging Member States to ensure that all household customers, and, where Member States deem it appropriate, small enterprises (namely enterprises with fewer than 50 occupied persons and an annual turnover or balance sheet not exceeding EUR 10 million), enjoy universal service. The fourth electricity directive (which has to be transposed by 31st December 2020 into Member States’ legislation) slightly modified the USO clause by repealing the ’small enterprises’ classification thresholds (related to the number of occupied persons and the annual turnover/balance sheet).

While the measures of the first energy package did not contain any social provisions, their subsequent amendments brought significant changes in this respect as well. The second electricity[vi] and gas[vii] directives empowered Member States to take special measures for vulnerable costumers, including the protection of final customers in remote areas. The third energy package elaborated this authorisation further by providing that „each Member State shall define the concept of vulnerable customers which may refer to energy poverty and, inter alia, to the prohibition of disconnection of electricity to such customers in critical times”.[viii] Additionally, in the gas sector, the lack of USO provision has been compensated by broader consumer protection instruments by obliging Member States to take measures on the formulation of national energy action plans that provide social security benefits to ensure necessary gas supplies to vulnerable customers and to address energy poverty, ‘including in the broader context of poverty’. Thus, the general social security system instead of a specific universal service obligation is preferred here (Sauter, 2014, 200). (An identical provision was also included by the third electricity directive, it has, however, a less significant role due to the existence of a separate USO clause in this directive.) The fourth electricity directive devotes a separate provision to vulnerable costumers. The new Article 28 adds a further element to the existing concept (see above) by saying that „The concept of vulnerable customers may include income levels, the share of energy expenditure of disposable income, the energy efficiency of homes, critical dependence on electrical equipment for health reasons, age or other criteria.”

As regards other rights granted to users, EU energy legislation also introduced an extensive consumer protection regime. The second electricity and gas directives already contained detailed provisions on consumer protection measures (both directives in a separate Annex A). One is that consumers have a right to a contract with specified elements laid down in Annex A, and the service provider must communicate in advance, to consumers, the specific information to be included in the contract. Moreover, service providers must publish information about tariffs and terms/conditions applicable in their relations with clients and a wide choice of payment methods must be granted. Customers must also be warned about their rights regarding the provision of the universal service (Nihoul, 2009). Furthermore, a dispute settlement mechanism was introduced, authorizing the regulatory authority to take decisions on complaints against transmission or distribution system operators, in the framework of „transparent, simple and inexpensive procedures”. This set of rights was supplemented by further ones in the third electricity and gas directives such as the right to be able to switch their energy contracts within three weeks. The electricity directive also laid down a general objective that at least 80% of the consumers must be equipped by intelligent metering systems by 2020. The fourth electricity directive went even further by inserting a separate chapter on consumer empowerment and protection.[ix] It includes, among others, the right to join a citizen energy community, the right to a dynamic price contract (based on prices in the spot or day-ahead market) and the right to request the installation of a smart meter within 4 months.

3 The impact of energy packages on national legislation: The challenges of price regulation

Although we can see in all the three sectors that subsequent measures developed into a more and more extensive and detailed regulation of consumer’s rights, it remains a question, whether the specific provisions are able to grant a real safeguard for consumer interests in any case.

As was already mentioned, ensuring access to basic public services at affordable prices is an essential element of a universal service obligation. The question is, first and foremost, whether the requirement for granting affordable consumer prices is able to be met in a liberalized market, without any public intervention. In the early 2000s, central regulation of energy prices still existed in the majority of EU Member States, often explained by the rising oil prices on the international markets and therefore the need to prevent consumers from paying the increased cost of the raw material. The European Commission, in its communication of 2007 summarising the experiences after adoption of the second energy package, established that intervention in gas (and electricity) pricing was simultaneously one of the causes and one of the effects of the current lack of competition in the energy sector. The Commission saw, on the one hand, ‘regulated prices preventing entry from new market players’ among the main obstacles in the transposition of the second energy and gas directives. On the other hand, it also highlighted that, as a result, ‘incumbent electricity and gas companies largely maintain their dominant positions’, which had ‘led many Member States to retain tight control on the electricity and gas prices charged to end-users’.

With the aim of reconciling the interest of liberalization and the need to ensure access for consumers to public services, the possibility of intervention in the price of supply is contemplated in the electricity and gas directives as well. From the adoption of the second energy package onwards, Member States are expressly permitted to impose public service obligations on undertaking operating in the electricity and gas sectors, which may in particular concern „the price of supplies”. In this context, it is also emphasized that „public service requirements can be interpreted on a national basis, taking into account national circumstances […]”. In addition, the gas directive authorizes Member States to take „appropriate measures” to protect final costumers, especially vulnerable ones, and to ensure high levels of consumer protection. Such an authorisation is inherent in the universal service obligation provided by the electricity directive, including the obligation to protect the right of consumers to be supplied with electricity at reasonable prices.

Though certain forms of price regulation (cutting utility fees etc.) might be among the most serious interventions into market trends, the CJEU interprets the scope of the above authorizations quite broadly. In the Federutility case, Italy adopted a Decree Law in 2007 (just a few days before 1 July, which was the deadline for completing the liberalization of the gas market under the second gas directive) which allocated to the national regulatory authority the power to define ’reference prices’ for the sale of gas to certain costumers. The reference prices had to be incorporated by distributors and suppliers into their commercial offers, within the scope of their public service obligations. The CJEU established that the second gas directive did not preclude national legislation of this kind provided that certain conditions (aiming at safeguarding competition on the gas market) defined by the Court were met.[x] In its ANODE judgment of 2016 (issued in a case concerning regulated gas prices in France), the CJEU extended the application of the principles set out in the Federutility ruling to the third gas directive too.

Although the Federutility judgment is generally seen as largely reducing Member States’ powers in price regulations, some notes should be taken in this regard. Firstly, the CJEU has not defined its position on the legality of the Italian legislation but left the final decision to the national court (submitting the request for preliminary ruling). As a result, the Italian regime survived the CJEU procedure and remained, with some modification, in force (Nagy, 184; Cavasola–Ciminelli [2012] 114.). Secondly, it is doubtful, whether the Federutility ruling encompasses only general industry-wide price regulation or it extends also to prices secured through a universal service provider (Nagy, 184). The question is crucial since, although natural gas is not considered to be an EU universal service, quite a few Member States characterize it as such (Nagy, 184) as the gas directive neither contains a prohibition to do this. Finally, the ’Federutility test’ seems rather to be able to filter obvious breaches of the above principles only (like in the Commission v Poland case) and not to address complex or structural problems which might be hidden behind well-formulated national provisions.

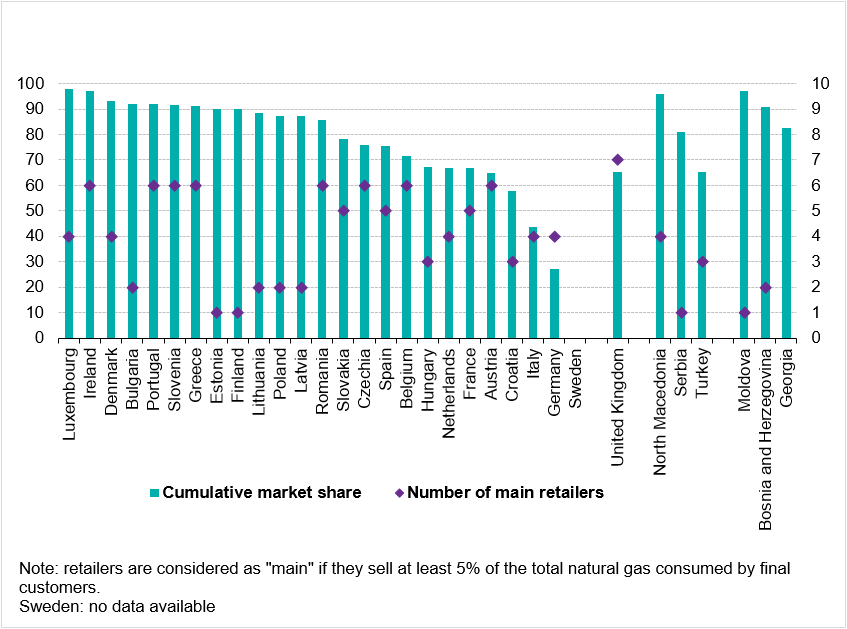

When evaluating the impact of subsequent energy packages and relevant CJEU case-law from a consumer perspective, one must consider the development of retail electricity and gas markets in recent years. A high number of suppliers and low market concentration is viewed as the indicators of a competitive market structure. CEER (Council of European Energy Regulators) data of 2014 show that retail electricity and gas markets for households were still highly concentrated in more than 2/3 of the EU Member States and the situation has remained largely unchanged in the last few years. In 2019, Hungary, Lithuania, Croatia and Luxembourg recorded the highest values (between 95% and 100% concentration rate). Figure 1 illustrates the number as well as the cumulative market shares of main natural gas retailers[xi] to final (not only household) costumers for 24 EU Member States and the United Kingdom in 2018. As we can see, in the majority of Member States, the retail natural gas market is dominated by a limited number of main retailers, while the market coverage of non-main companies is below 40% in almost all the countries (except of Croatia, Italy and Germany).

Figure 1. Number of main natural gas retailers to final customers and their cumulative market share, 2018

Source: Eurostat

According to data from 2019, public price intervention still exists in certain Member States, both in the electricity and the gas sectors. 80% of these countries reported that the reason for intervention in the price setting is the protection of consumers against price increases. The long-term market impact of these measures may even be detrimental to consumers themselves. The ability of users to effectively make choices between suppliers is one of the key indicators for a well-functioning energy retail market. Such an ability is often measured by switching rate which is calculated by dividing the number of consumers who switched suppliers in a given period by the total number of consumers on the market. In line with the Commission’s observation quoted above, today it is also true that countries with regulated retail prices tend to have lower levels of retail competition as regulated prices discourage entry and innovation, increase suppliers’ uncertainty regarding long term profitability levels and reduce consumers’ incentive to switch supplier. CEER data of 2016 show a clear correlation between the share of household customers under regulated prices and the average number of suppliers per citizens. It is also indicated that switching rates in Member States that have either deregulated or had a minority share under regulated prices are substantially higher than in markets where a majority of households are under regulated prices, both in the electricity and the gas sectors. According to the ACER (European Union Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators) Market Monitoring Report of 2019, regulated prices are in the first place among regulatory barriers of switching.

In sum, the above analysis suggests that interventionist measures taken by Member States for the protection of consumers rather strengthen a way towards fragmentation than integration of energy retail markets. Moreover, the gradually extension of Member States’ power to deviate from the general rules of the energy directives on the basis of the social legitimacy of such measures (as laid down by the directives themselves) may hide further dangers for the functioning of the internal market. In particular, the objective of consumer protection may be (mis)used to hide the initial aim of certain forms of public intervention (like price regulation having the effect of excluding targeted actors from the market).

Conclusions

At the beginning stage of the European integration, the ‘consumer’ has fallen outside the realm of SGI regulation at the EU level, since public services sectors were traditionally organized and financed by states or public entities without being open to competition in international markets. This approach has changed in the mid-eighties, with an extensive liberalization process engaged by the Single European Act which also extended to significant economic sectors of public services such as electricity, gas, water supply or waste management. The ‘paradigm shift’ has also changed the position of the consumer from a mere ‘user’ to be supplied to a relevant market actor. Initially, the liberalization program was based on the presumption that the interests of consumers could best be served via the processes of market opening and competition, unless the pursuit of other legitimate objectives beyond competition and free trade was in itself justifiable (Johnston, 2016, 95). Over time, the scope and significance of these ‘other objectives’ increased. This is particularly true for the energy sector, where the protection of consumers (especially vulnerable ones) gradually received a higher rank in the legislative packages. In this line, Member States’ power to safeguard consumer interest by measures deviating from the general rules of sector liberalization has also been extended.

The examples analysed in the paper have also shown that the interest of consumer protection is able to legitimize not only the promotion of liberalization (as was stated by the above mentioned authors) but also the extension of national regulatory competences in the field of public services. The relevant European legislative framework also supported this line of evolution or at least it did not raise any serious obstacles to enhance Member States’ powers, even to the detriment of consumers.

For a list of references, click HERE.

Author: Ildikó Bartha, Senior Research Fellow, MTA-DE Public Service Reserch Group; Associate Professor, University of Debrecen, Faculty of Law

[*] The study was made under the scope of the Ministry of Justice’s program on strengthening the quality of legal education.

[i] See Article 36. Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union.

[ii] See for instance Directive 1999/44/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 May 1999 on certain aspects of the sale of consumer goods and associated guarantees, OJ L 171, 7.7.1999, pp. 12-16, Art. 1(2)(a)

[iii] Term borrowed from Bauby and Similie (2016a, 27).

[iv] ECLI:EU:C:2009:640

[v] Directive 96/92/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 December 1996 concerning common rules for the internal market in electricity, OJ L 27, 30.01.1997 pp. 20–29, Art. 3(2); Directive 98/30/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 June 1998 concerning common rules for the internal market in natural gas, OJ L 204, 21.7.1998, pp. 1–12

[vi] Directive 2003/54/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 June 2003 concerning common rules for the internal market in electricity and repealing Directive 96/92/EC, OJ L 176, 15.7.2003, pp. 37–56

[vii] Directive 2003/55/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 June 2003 concerning common rules for the internal market in natural gas and repealing Directive 98/30/EC, OJ L 176, 15.7.2003, pp. 57–78

[viii] Directive 2009/72/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 July 2009 concerning common rules for the internal market in electricity and repealing Directive 2003/54/EC, OJ L 211, 14.8.2009, pp. 55–93, Art. 7(3); Directive 2009/73/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 July 2009 concerning common rules for the internal market in natural gas and repealing Directive 2003/55/EC, OJ L 211, 14.8.2009, pp. 94–136, Art. 3(3)

[ix] Directive (EU) 2019/944 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 June 2019 on common rules for the internal market for electricity and amending Directive 2012/27/EU, OJ L 158, 14.6.2019, pp. 125–199, Art. 10–29

[x] These conditions are the following: the intervention constituted by the national legislation (1) pursues a general economic interest consisting in maintaining the price of the supply of natural gas to final consumers at a reasonable level; (2) compromises the free determination of prices for the supply of natural gas only in so far as is necessary to achieve such an objective in the general economic interest and, consequently, for a period that is necessarily limited in time; and (3) is clearly defined, transparent, non-discriminatory and verifiable, and guarantees equal access for EU gas companies to consumers.

[xi] Retailers are considered as “main” if they sell at least 5% of the total natural gas consumed by final customers.