Hungary became part of the European Union (EU) during the 2004 ’big bang’ enlargement together with nine other, predominantly Central and Eastern European countries. The accession of new Member States brought crucial legal, economic, and social changes in the acceding countries, including Hungary. EU accession triggered remarkable interactions between EU law and the domestic law of the acceding countries. Read more… (Petra Ágnes Kanyuk)

Hungary became part of the European Union (EU) during the 2004 ’big bang’ enlargement together with nine other, predominantly Central and Eastern European countries. The accession of new Member States brought crucial legal, economic, and social changes in the acceding countries, including Hungary. EU accession triggered remarkable interactions between EU law and the domestic law of the acceding countries. Read more… (Petra Ágnes Kanyuk)

Hungary became part of the European Union (EU) during the 2004 ’big bang’ enlargement (Matthews-Ferrero, 2019.) together with nine other, predominantly Central and Eastern European countries. The accession of new Member States brought crucial legal, economic, and social changes in the acceding countries, including Hungary. EU accession triggered remarkable interactions between EU law and the domestic law of the acceding countries (Szabados, 2018, 41.).

The Largest Round of Enlargement in the EU’s History

As well as Hungary, the other countries joining the EU on 1 May 2004 were Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Poland, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Slovakia, and Slovenia, making this EU enlargement the largest round of enlargement to date. The establishment and tightening up of institutional relations with the EU – the “eastern enlargement project” – started in the period before this date: it is well-known that, following the change of regime in the Eastern European region in the early 1990s and after the end of the Cold War, all countries applied for membership of the EU almost immediately. European economic integration was already visible in the way the internal market was functioning in the EU Member States, in Western European countries; economic development and the emergence of social welfare were also desirable goals for the countries in question.

As well as Hungary, the other countries joining the EU on 1 May 2004 were Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Poland, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Slovakia, and Slovenia, making this EU enlargement the largest round of enlargement to date. The establishment and tightening up of institutional relations with the EU – the “eastern enlargement project” – started in the period before this date: it is well-known that, following the change of regime in the Eastern European region in the early 1990s and after the end of the Cold War, all countries applied for membership of the EU almost immediately. European economic integration was already visible in the way the internal market was functioning in the EU Member States, in Western European countries; economic development and the emergence of social welfare were also desirable goals for the countries in question.

Already at that time, the accession procedure had a well-established legislative and policy background. In this framework, the EU established the system of relations between the Communities and Central and Eastern European countries, including Hungary, by providing trade policy preferences, developing guidelines for political dialogue, and harmonising domestic laws and regulations with EU law. The moves towards accession were supported by a broad-based EU financing programme. The EU gave up using safeguarding measures in trade against the former socialist countries and offered asymmetric preferences to them, in other words, the Community had broken down the customs barriers to candidate countries. The ‘second-generation’ association agreements, also called new-type association agreements, provided the legal basis for the Eastern enlargement, and contained only a very few country-specific features in various documents of an identical structure.

It is important to point out that the Copenhagen criteria were formulated in this period – they were established by the Copenhagen European Council in 1993 and strengthened by the Madrid European Council in 1995 – and in addition to setting economic, social and political prerequisites for the countries aspiring to join the EU, they also marked directions for the entire EU’s development. They have remained validly applicable to any country wishing to accede to the EU ever since (Marktler, 2006, 343.). The Treaty on European Union sets out the conditions (Article 49) and principles (Article 6(1)) to which any country wishing to become an EU member must conform. Certain criteria must be met for admission. They are:

- stability of institutions guaranteeing democracy, the rule of law, human rights and respect for and protection of minorities;

- a functioning market economy and the ability to cope with competitive pressure and market forces within the EU;

- ability to take on the obligations of membership, including the capacity to effectively implement the rules, standards, and policies that make up the body of EU law (the ’acquis’), and adherence to the aims of political, economic and monetary union.

For EU accession negotiations to be launched, a country must satisfy the first criterion.

The countries which joined the EU at the same time started the accession procedure and negotiations on different dates and with different prospects. Following the transformation of the political system, Hungary and Poland were the closest to accession. After Czechoslovakia was split up, the Czech Republic and Slovakia also submitted their formal applications for accession. The parties had to negotiate 31 accession chapters, and the discussions were bilateral (Pintér, 2018, 167.). The association agreements were concluded within a few years, but accession negotiations were delayed – they were started in 1998 between Hungary, several Central and Eastern European countries (not all that acceded in 2004), and the EU and completed in 2002. The Treaty of Accession was finally signed in Athens on 16 April 2003. It is also noted that during the enlargement, the candidate countries were initially divided into two groups, however, a decision was made in 2004 to include eight former socialist countries (Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Slovenia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia), and two island countries, Cyprus and Malta, in the EU. Bulgaria and Romania, treated as candidate countries for a time in the procedure, could only join the EU in 2007.

The Hungarian Perspective

From the Hungarian point of view, the agreement with the EU was the part of a general policy of opening up to Western structures. The country had been admitted to the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank in 1982, and in the late 1980s, the last government of the old regime also established contacts with the European Parliament and applied for membership of the Council of Europe (Lengyel, 1994, 354.). In the course of the accession negotiations, Hungary certainly had to fulfil a large number of criteria included in accession chapters; and the political deals and legislative harmonisation laid the basis for Hungary to be able to succeed as an EU Member State. Hungary’s path to membership in the European Union was characterized by the fact that the most important goals to be achieved and tasks to be accomplished predominantly included the establishment of political sovereignty, the economic policy interventions and the institutional system of a market economy (Butler, 2007, 1115.).

From the Hungarian point of view, the agreement with the EU was the part of a general policy of opening up to Western structures. The country had been admitted to the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank in 1982, and in the late 1980s, the last government of the old regime also established contacts with the European Parliament and applied for membership of the Council of Europe (Lengyel, 1994, 354.). In the course of the accession negotiations, Hungary certainly had to fulfil a large number of criteria included in accession chapters; and the political deals and legislative harmonisation laid the basis for Hungary to be able to succeed as an EU Member State. Hungary’s path to membership in the European Union was characterized by the fact that the most important goals to be achieved and tasks to be accomplished predominantly included the establishment of political sovereignty, the economic policy interventions and the institutional system of a market economy (Butler, 2007, 1115.).

Before Hungary acceded to the EU, the representatives of the entire legal profession were excited about the EU accession and what legal challenges it could bring. They were full of anticipation about the time when EU law would wash over the national legal and judicial system. Some looked forward to the process with interest, some with aversion (Kovács, 2019, 7.). There is a wide range of approaches to integration, of course: in addition to the legislative, political, and social dimensions, economic integration is also a legitimate, scientifically used and discussed concept. Its membership has had a positive impact on the Hungarian economy and provided several competitive advantages for foreign companies setting up a permanent presence in the country.

Looking Back, Looking Forward – Six Trends, with Particular Regard to Hungary

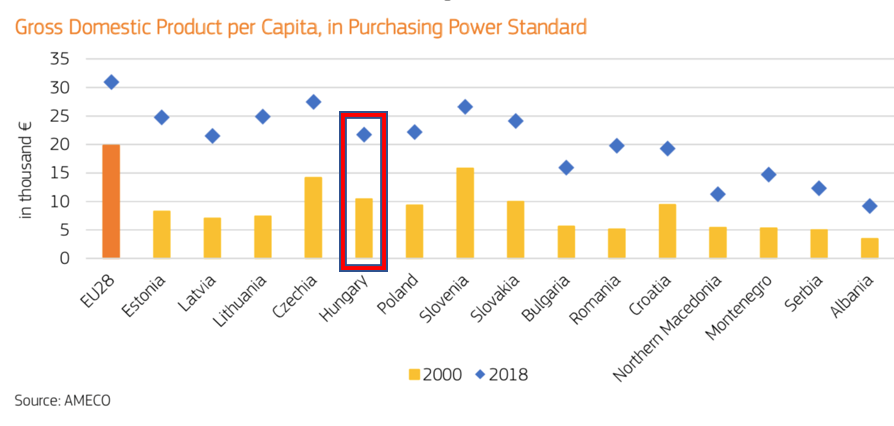

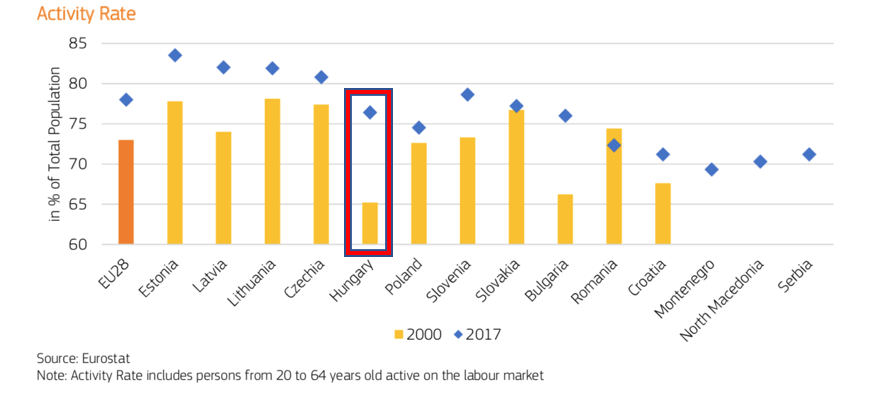

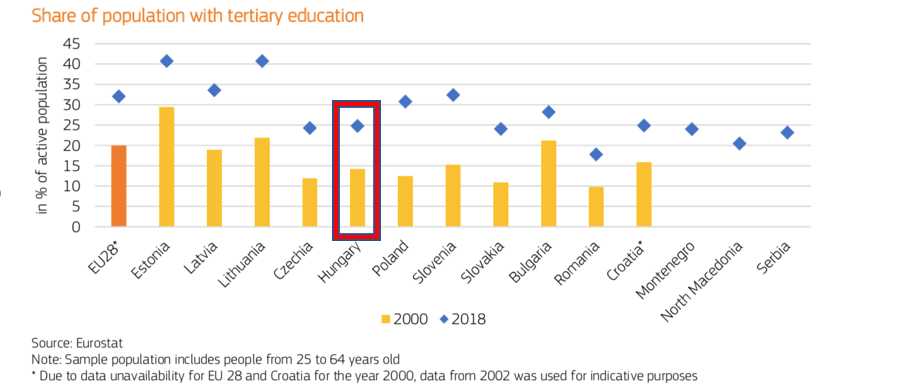

The following figures highlight the central improvements among the new Member States between 2000 and 2018. To include a forward-looking element, the charts contain whenever possible the candidate countries from South-East Europe.

1. Income convergence to the European average

On average, GDP per capita (at purchasing power parity) in the new Member States has risen 250% since 2000, compared to ‘just’ 50% for the EU as a whole. This trend is visible across the board, GDP per capita in all the new Member States has converged towards the EU average at a fast pace and is now above 70% in all the countries that joined in 2004. The candidate countries are also catching up but the gap remains significant. In the case of Hungary, the GDP per capita of just over 10 thousand euros in 2004 jumped to around 22 thousand euros by 2018, which rivals the Latvian and Polish data and is slightly above the Romanian and Bulgarian data.

2. Participation rates eclipse the EU average

Employment levels have risen sharply in both the old and new Member States in recent decades. Activity rates are now over 70% in all the new Member States and some boast levels significantly above the EU average. One of the biggest and most welcome improvements in Hungary was the rate in question, i.e. the labour market activity rate of the 20-64 age group (employed or declared unemployed compared to the total population), as we can see: in 2000 the rate was 65% – and it was the lowest of all Member States – but it jumped to 77% last year.

3. Convergence in educational attainment

The share of those with tertiary education or with advanced vocational training in the new Member States has increased, particularly in those that were the furthest behind at the turn of the century. Most new Member States are now close to the EU average. In Hungary, the level of progress is also significant, as the Hungarian figure rose from less than 15% to 25% from 2000 to 2018.

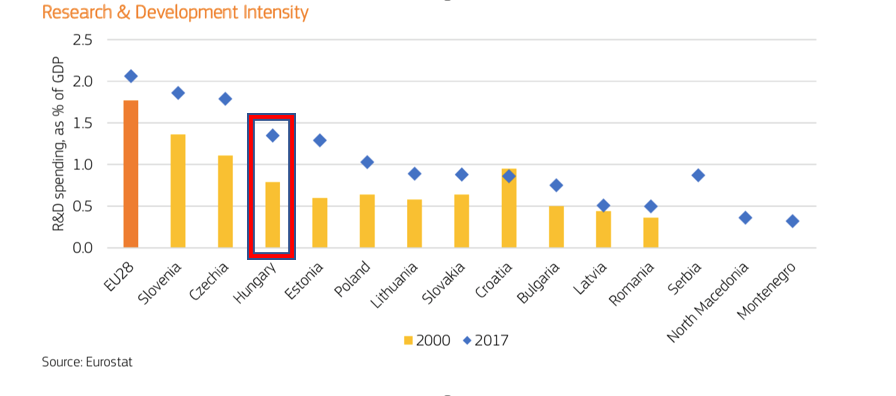

4. Research, Development, and Innovation

The ratio of R&D and innovation expenditures to GDP has risen in most new Member States, supported by EU funding schemes such as Horizon and COSME. It increased significantly from 2000 to 2017 (from around 0.8% to around 1.4%), placing Hungary in third place among the dozen countries examined, followed by Estonians.

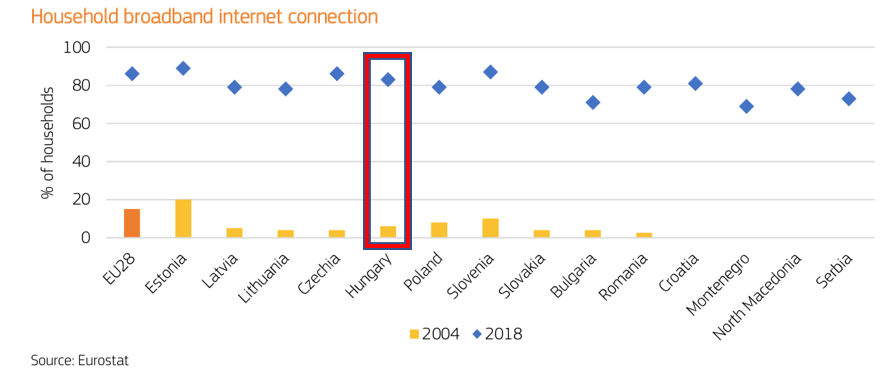

5. Digital connectivity

Households in the region are more connected than ever. Internet connectivity rates have risen sharply in the new Member States since they joined the EU and are now close to the EU average in most cases in no case less than 80%. By 2018, Hungary managed to achieve the EU and essentially the same regional average (81%) among households in terms of broadband internet coverage. Since in the meantime broadband coverage reached the entire country, this ratio is expected to increase further.

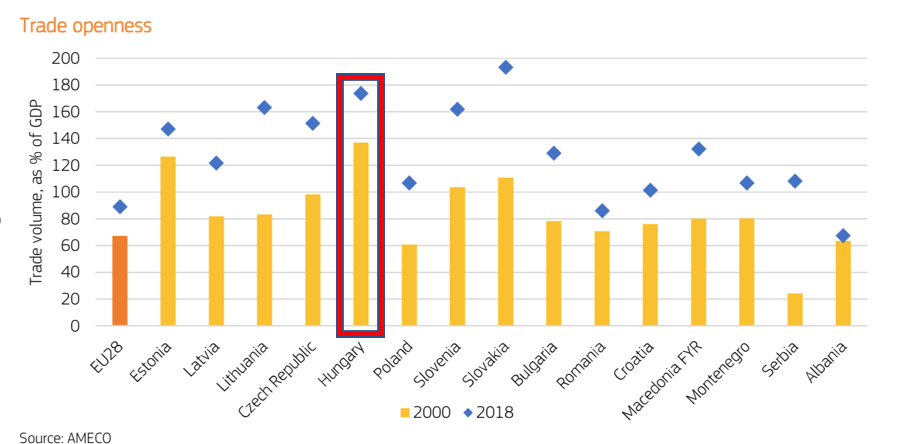

6. Openness to trade and integration into European supply chains

With new trade opportunities arising from single market access and EU trade agreements with third countries, the new Member States have become more globally integrated, as exemplified by their increased trade openness. We often hear that Hungary’s economy is small and open, and the figure below shows this well; since the annual exports and imports together reach almost 180% of GDP, the second-highest rate among the countries examined after Slovakia. In the case of Hungary, this indicator was already extremely high in 2000, specifically, it was the highest of all the examined countries (about 137%), so the further increase in the proportion was not as large as in several countries in the region. Interestingly, the Romanian figure is ‘only’ 85%, which is broadly in line with the EU average.

Closing Remarks

Sixteen years ago, when Hungary became a member of the EU, the majority of Hungarian legal professionals had not yet to realise the impact this fact would have on the domestic legislation and justice as well (Czine, 2014, 20.). The importance that all legal professionals have proper knowledge in this special area of the interaction between domestic law and the EU law as well cannot be stressed enough in the stream of the current situation (Karsai, 2004, 90.), especially in the light of the fact that the EU is proceeding towards the realisation of the single area of justice (Polt, 2019, 14.), and the endeavours of the EU appear in the deepening of legal harmonisation and the uniformisation of substantive and procedural law instruments as well.

We have to acknowledge that the national law cannot be exempted either from the influence of the EU law. The issues under examination are present simultaneously on the theoretical and/or practical level, thereby vesting a serious task on the EU and the Member States, therefore on all the bodies concerned of our country (Polt, 2019b, 332.).

It would be an impossible mission to summarise the legislation changes owed to Hungary’s accession to the EU in one single study. For this very reason, the following studies will be a ‘bouquet’ of some outstanding sections of the Hungarian achievements, which may highlight the essence of the process and support the constant change of the field in question.

For a list of references, click HERE.

Author: dr. Petra Ágnes Kanyuk

Ph.D. Student at the Géza Marton Doctoral School of Legal Studies of the University of Debrecen, Department of Criminal Law and Criminology

The study was prepared with the professional support by the Research Scholarship for Ph.D. Students No. ÚNKP-19-3, granted by the Ministry for Innovation and Technology in the framework of the New National Excellence Programme.