Corporations have been undertaking very risk-taking activities abroad. Since they are met with less protective legislations in third-countries, some subsidiaries have been conducting their business without proper respect for human rights. As a result, not only the subsidiaries but also the parent companies can be held liable for violations of such rights in civil proceedings in their home countries. However, there is no standard international convention or jurisdictional body to regulate the relation between business and human rights and the legal remedies that victims can access. In this regard, victims must call upon domestic courts in a pursuit of the most favorable jurisdiction to obtain a civil legal redress mechanism. Read more… (Rafael Lima Asche)

Corporations have been undertaking very risk-taking activities abroad. Since they are met with less protective legislations in third-countries, some subsidiaries have been conducting their business without proper respect for human rights. As a result, not only the subsidiaries but also the parent companies can be held liable for violations of such rights in civil proceedings in their home countries. However, there is no standard international convention or jurisdictional body to regulate the relation between business and human rights and the legal remedies that victims can access. In this regard, victims must call upon domestic courts in a pursuit of the most favorable jurisdiction to obtain a civil legal redress mechanism. Read more… (Rafael Lima Asche)

by RAFAEL LIMA ASCHE

Legal framework

Business and human rights law have recently become interconnected. As a rule, western legislations do not tend to include legal norms about the corporate behavior abroad. At an international level, the UN has published the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights of 2011 on the implementation of the “Protect, Respect and Remedy” framework. Nonetheless, as it consists in a set of guidelines, the voluntary basis prevails. In this sense, an international convention about this topic is still pending, and so is a proper legislative body directed to corporate torts for gross violations of human rights only (van Dam, 2011: 225-227).

Many corporations who wish to expand their business abroad resort to risk-taking activities through subsidiaries. Since protective legislations outside Europe and the USA can sometimes be not so efficient, violations such as forced labor, killings, torture, negligent supervision of health of workers, damages to land, constantly occur. In this scenario, not only the subsidiaries can be held liable, but also their parent companies due to a breach of the duty of care.[1]Therefore, victims will have more than one possibility to obtain legal redress. Attempting to hold parent companies liable for human rights violations as complicit of their subsidiaries might be efficient. However, choosing the proper jurisdiction is a crucial factor and, thus, forum shopping will play an important role in this context.

The subject in the USA and in Europe

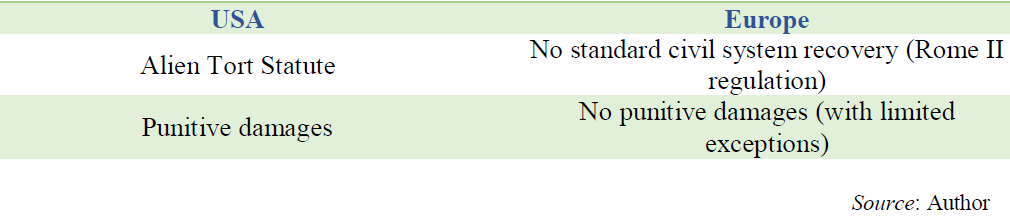

As a starting point, it is relevant to note that this topic is much more developed in the USA than in Europe. The avenue through which such human rights violations will find a judicial access in America is the Alien Tort Statute of 1789 (ATS)[2]. In Europe, differently, a civil recovery system for human rights violations such as in the USA has not yet been developed. Thus, while plaintiffs alleging corporate torts for violations of human rights will have a specific legislation and a competent judicial mechanism in the USA, in Europe states will have to observe the Rome II Regulation, which sets choice of law for foreign torts. Its general rule is that the applicable law should be the one from the country where the damage occurred, unless there are strong reasons to apply legal sources from another jurisdiction, for example on the grounds of public policy (Zerk, 2016, 50-51).

Hence, the first impression is that the ATS might make the American litigation more suitable for the victims of corporate torts. Another fact that might make the American jurisdiction attractive is the existence of punitive damages, which can result in huge awards for the victims. Since punitive damages are connected to the common law system, in continental Europe the final compensation would not be comparable in pecuniary terms. Besides, even in the UK and in Ireland recovery of punitive damages is rare (Fausten & Hammesfahr, 2012: 2). Subsequently, we can associate this particularity with the American jurisdiction. Despite those advantages, American case law is not always consistent, and this jurisdiction is not necessarily the best alternative, as we will analyze in the next chapter.

In summary, the table below presents the essential differences between the situation in the USA and in Europe on how different jurisdictions respond to corporate torts in relation to violations of human rights.

Table 1. Civil legal redress

How does forum shopping really work? The Royal Dutch Shell case

Case law for business and human rights shows that choosing a more favorable jurisdiction can lead to extremely different results for the victims. In this regard, we can better illustrate how forum shopping works in this panorama by analyzing the proper case law.

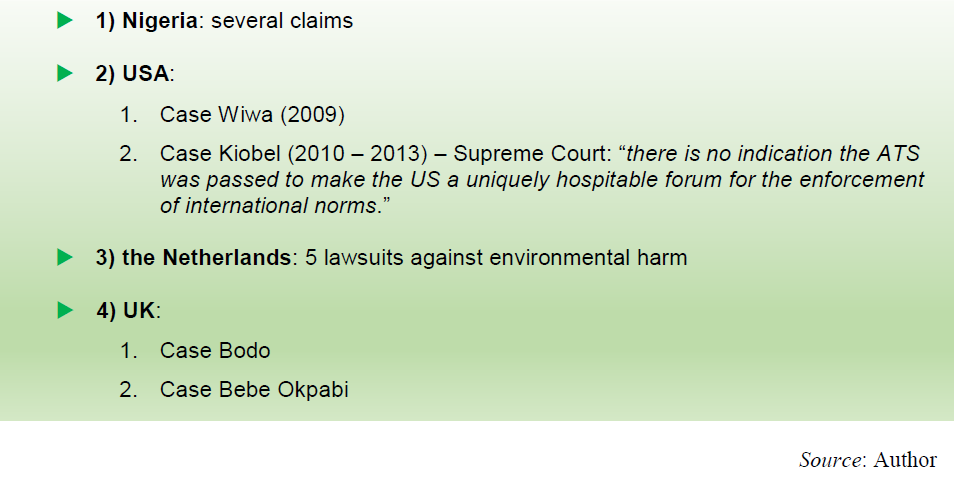

The following lawsuits are related to the giant oil company with joint British and Dutch stock market listings and with headquarters in both countries. In 1958 Shell began exploiting oil in Nigeria, which will be the background for the following litigations. This event involves the following jurisdictions: Nigeria, the Netherlands, the UK, and the USA (Blackburn, 2017: 21-24).

Initially, it is convenient to mention that many claims have been initiated in the Nigerian courts against Shell’s subsidiary incorporated in Nigeria. However, many problems such as delay, effectiveness, and economic influence have led plaintiffs to seek judicial redress in the USA and in Europe (Blackburn, 2017: 22).

The first case we should mention was litigated in the USA. In Wiwa v Royal Dutch Shell[3], it was alleged that Shell was complicit in military operations against the Ogoni people, which is an indigenous group from Southeast Nigeria (Newman, 2002). The families sought justice in the USA based on claims of corporate complicity. In 2009 there was a settlement and Shell agreed to pay US$ 15 million (Meeran, 2011: 2). As we can observe, forum shopping was effective in terms of providing reparation in this case.

Contrarily to the previous case, in 2010 the US Second Circuit Courts of Appeals stated in Kiobel v Royal Dutch Petroleum Co that customary international human rights law does not recognize the liability of corporations (van Dam, 2011: 233). In 2011 that Court held, moreover, that the jurisdiction granted by the ATS does not extend to civil action against corporations. Finally, in 2013 the Supreme Court stated that the matter in question was another. It decided that mere corporate presence is not sufficient, since the defendants are not American companies and since petitioners seek relief for violations occurred outside the USA. ATS can, therefore, hold defendants liable only when the case touches and concerns the US with sufficient force. The court states, besides, that “there is no indication that the ATS was passed to make the United States a uniquely hospitable forum for the enforcement of international norms.”[4] Currently, Ms. Kiobel is attempting to proceed against Shell in the Netherlands, since after the dismissal of Ms. Kiobel’s case by the Supreme Court of the United States in 2013 a Dutch law firm took on the case and commenced proceedings in the Netherlands by serving a writ of summons last year.

As we can see, despite the fact that the USA possesses a specific civil recovery system, sometimes case law can diverge, and the American jurisdiction might not necessarily be a better decision than the European ones. In this regard, there were also five lawsuits initiated in the Netherlands against the Nigerian subsidiary and its parent company on the grounds of breach of the duty of care to protect from environmental harm caused by the spills from pipelines (Blackburn, 2017: 22-23). Four out of the five cases were dismissed by reason that there was a situation which included a third-party sabotage and poor maintenance, but under Nigerian law (applicable according to the Rome II Regulation) the subsidiary was liable only for the latter. In the remaining case, the tort of negligence was recognized due to the violation of the duty of care. Nevertheless, all claims against the parent company were dismissed based on Nigerian law. The Court of Appeal overturned the decisions and held that the home state courts had jurisdiction based on the EU jurisdictional rules in the Brussels Regulation. The process is still on-going.[5]

Two more cases are relevant to mention in the Shell context. The first one is Case Bodo, which was litigated in the UK High Court seeking compensation for around 11,000 claimants.[6] On a preliminary hearing, the Court ruled that the parent company could be held liable if it failed to protect the plaintiffs either from the subsidiary’s failure or from a third party. Before a full trial could be heard, Shell agreed in a settlement to pay £55 million in 2015 (Blackburn, 2017: 23-24). In this case, therefore, the British jurisdiction was a good choice to achieve reparation for the victims.

Contrasting with the previous case, we should allude to Case Bebe Okpabi (claim initiated by the Nigerian king), equally litigated in the UK High Court and consisting of two claims seeking compensation for around 42,500 people. In 2017, the Court declined jurisdiction holding that the Chandler duty of care proviso[7] was not present in this case. The Court held that, following a corporate restructuring, the parent company lacked technical expertise and had no considerable supervision over the subsidiary, resulting in no duty of care.[8]As we can see, case law in the UK can also be divergent and, thus, predictability is extremely hard in those situations.

Table 2. Forum shopping in Shell case

Summarizing the impressions

Corporations have increasingly been required to comply with standards established by international human rights law. Even though there is no international agreement on the topic and the subject remains obscure in many details, we can say that civil litigation has been, in many cases, a successful mechanism to achieve a remedy for the victims. Also, although most of the cases are settled between the parties and not subject to a final judicial decision, they still are conclusive, because in many rulings the orientation of the courts is towards giving a positive affirmation of the corporate liability.

As discussed above, the ATS seems to be a very attractive mechanism against corporations, this being the reason why case law in the USA is more abundant than in Europe. As Bradley argues, some reasons why the ATS is attractive to plaintiffs are: a) corporations do not benefit from immunity doctrines like governmental defendants do; b) most large corporations have presence in the USA, making the jurisdiction problem easier; c) they have considerable assets that can be reached by the courts and also it works as an incentive for them to settle an agreement and avoid bad publicity (Bradley, 2010: 1825).

However, this tendency can lack predictability and efficiency, since American courts might diverge about the purpose of the ATS. Also, in some cases the European jurisdictions appear to be equally very effective. Therefore, forum shopping is a practice that really influences the reparation that victims can achieve. Perhaps the best alternative would be to have a standard system for such recoveries through a common convention as lex specialis and a proper jurisdictional body. Yet, since they are non-existent, it is important to seek the most favorable jurisdiction to achieve a reasonable remedy through the application of domestic liability laws.

To conclude, some factors should be taken into consideration when searching for the appropriate forum. In common law states, defendants often refer to the forum non conveniens doctrine.[9] This happens when the defendant presents a motion to dismiss the case holding that the most convenient or appropriate forum for the judgment would be another one. The result is a delay in the litigation or even a bigger hindrance in case of dismissal. In the UK this doctrine was also applied, but it was reduced because of its integration with the EU jurisdictional rules. Contrarily, it is also convenient to mention that some civil law jurisdictions, such as Germany, France, and Canada (Quebec), apply the doctrine of forum of necessity (forum necessitatis), which means that their courts can take jurisdiction over a case when it is understood that there is no other forum available to provide remedy for the victims, that is, it is a legal concept to prevent denial of access to justice (Zerk, 2016: 48-49).

For the list of references, click HERE

Author: Rafael Lima Asche, LL.M. Student, University of Debrecen

[1]See further Cassell, D. (2016). Outlining the Case for a Common Law Duty of Care of Business to Exercise Human Rights Due Diligence. Journal Articles, Business and Human Rights Journal 1263: 179-202.

[2] See further discussions on the ATS in Wright, R. G. (2016). Negotiating the Terms of Corporate Human Rights Liability under Federal Law. San Diego Law Review 53(3), pp. 587-592.

[3] See Wiwa v. Royal Dutch Petroleum Co., 2002 WL 319887 (S.D.N.Y. 2002).

[4]Kiobel v Royal Dutch Petroleum, No. 10-1491, 2013, 569 US Supreme Court, pp. 12-14.

[5]See Case 200.126.849-01 200.127.813-01 (2015),Gerechtshof den Haag (in Dutch).

[6]The Bodo Community and Others v Shell Petroleum Development Company of Nigeria Ltd [2014] EWHC 1973(TCC).

[7]A 3-level test for a duty to arise in English law: 1) if the harm was foreseeable; 2) if there was enough proximity between the parties; and 3) if it is fair, just and reasonable to impose a duty of care. Vide Chandler v Cape Plc [2012] EWCA Civ 525 (25 April 2012), para 32, and 62-81. This is also known as the Caparo test: vide Caparo Industries Plc v Dickman [1990] 2 AC 605, UKHL 2.

[8]His Royal Highness Emere Godwin Bebe Okpabi and Others v Royal Dutch Shell PLC and Shell Petroleum Development[2017] EWHC 89 (TCC), para 107-122.

[9]See, for instance, Wiwa v Royal Dutch PetroleumCo 226 F 3d 88 (2d Cir 2000).