Nowadays the system of child protection needs to face and cope with many challenges. These challenges are stemming from different sources, including the efforts of the government to renew and reinforce the child protection system and the related enactments and codification, the resource requirements of the professionals involved in the work of child protection or the capacity of the system. It is obvious that the system has to react and respond to these challenges. Read more... (Imre Bertalan)

Nowadays the system of child protection needs to face and cope with many challenges. These challenges are stemming from different sources, including the efforts of the government to renew and reinforce the child protection system and the related enactments and codification, the resource requirements of the professionals involved in the work of child protection or the capacity of the system. It is obvious that the system has to react and respond to these challenges. Read more... (Imre Bertalan)

Imre Bertalan

Nowadays the system of child protection needs to face and cope with many challenges. These challenges are stemming from different sources, including the efforts of the government to renew and reinforce the child protection system and the related enactments and codification, the resource requirements of the professionals involved in the work of child protection or the capacity of the system. It is obvious that the system has to react and respond to these challenges. The system needs to develop its unique coping mechanisms and its own responses. However, if we would like to examine and understand these mechanisms, we need new approaches, new methods and new interpretations. The present blog entry focuses on the child protection system[1]. During the last few years, significant changes have occurred in Hungary, – for example, the modifications in the context of legislation or the above mentioned examples – which affected the everyday task management of the child protection system.

Hereby we undertake to provide a detailed and comprehensive picture of the structure of the child protection system by introducing, processing and analyzing antecedents, to identify various connection points between agencies, institutions and organizations of different levels that all play a significant role in child protection – thus organizing a segment of the wide range of public services and public duties – and to present a method the application of which offers us a new way to interpret and understand the child protection system. We have to pay special attention – due to the nature of task management – to the issue of interpersonal relations and the work through interpersonal nexuses. It is probable that a deep, informal network lies between the authorities, agencies, institutions and organizations, and mainly between their employees, being involved in the everyday work of the child protection system – running parallel with the formal network based on legislation that can be identified objectively – because this system is not a network of independent individuals or institutions but rather a dynamic network and a complex social activity.

In case of such an approach, we should involve the dimension of social resources in the interpretation since this construction is very close to the social-network approaches being popular currently, and by its usage, we can highlight that the staff of the child protection system and the system itself operate embedded in a complex social network. By applying this framework of examination, we receive broad-scale public service sociometric feedback as well by revealing all the relations.

In connection with the above, during our investigation, we considered it particularly important to gain information and data through empirical, objective and repeatable methods since these are the minimum requirements of scientific investigations.

First we conducted interviews with the employees of institutions involved and playing an active role in child protection, particularly with the collective of the Social Service Center’s Child Welfare Service of an average middle-sized town of (Hajdúböszörmény) Hungary.. While defining the questions and the focus of the interview, we largely relied on the practical experience of the previous years. According to our initial hypothesis, our goal was to examine the social network lying between the service providers, institutions and authorities, listed explicitly by the ‘Child Protection Act’ of Hungary (Act XXXI of 1997 on Child Protection and Custody Administration) , attending to tasks related also to the system of child protection – for example the child welfare service, healthcare service providers, the police, the (specialized) nursing services or the labor authority.

While conducting the interviews and during the examination of their contents, it was revealed that the local child protection system is way more extensive than and somewhat different from the one stipulated in the legislation. We considered it to be important not to base our later empirical research on the significantly structured and bound institutional-organizational system but to try to reveal the specific local relations and the possible points of relations between institutions.

For this reason, we have conducted a content analysis on the texts of the interviews, which is a research tool and method, with the help of which we can access less structured but more subjective information concerning the cognitive representation of the participants, in relation to the local child protection system. Due to the unstructured information, the free response form and the very high level of subjectivity, we received data that can be evaluated both from a qualitative and quantitative aspect. We have to emphasize that the content analysis has to be context-sensitive (Krippendorf, 1999, 2013; Ehmann, 2002) and we have to consider the question-answer pair as a unit, the internal structure of which can be judged as significant.

Table 1.

The List of Institutions after the Content Analysis

| Institutions | |

| 1. | Family Support Center of the Social Service Center |

| 2. | Csillagvár Nursery School |

| 3. | University of Debrecen Practicing Nursery School (in Hajdúböszörmény) |

| 4. | Child Welfare Service of the Social Service Center |

| 5. | Unified Pedagogical Specialized Services of Hajdúböszörmény |

| 6. | Kincskereső Nursery School of Hajdúböszörmény |

| 7. | Department for Human Policy and Administration of the Major’s Office in Hajdúböszörmény |

| 8. | Police Office of Hajdúböszörmény |

| 9. | Pediatrician |

| 10. | District Guardianship Office of Hajdú-Bihar County’s Government Offices, District Office of Hajdúböszörmény |

| 11. | District Public Health Institute of Hajdú-Bihar County’s Government Offices, District Office of Hajdúböszörmény |

| 12. | Jó Pásztor Reformed Nursery School |

| 13. | Katica Families’ Temporary Home |

| 14. | School District of the Klebersberg Institute Conservation Center in Hajdúböszörmény |

| 15. | Napsugár Nursery School |

| 16. | City Day Nursery |

| 17. | Chief Medical Officer of the City |

| 18. | Nursing Services |

Table 1. contains the list of institutions as it appears as a result of content analysis following the previously presented interviews. It is visible that this is somewhat different from the institutions and authorities participating in child protection tasks, listed exhaustively in the Child Protection Act relevant from the aspect of our research, so much that some of the actors appearing in the Act were not even mentioned. It is worthwhile to note that this correlates with our initial assumptions, according to which, this social network operates embedded in its own context, despite the dominant centralization efforts, that can almost be called rigorous and which exist in today’s economics and, especially in the system of child protection.

As the next step of the empirical research, we prepared a sociometric survey along the guidelines indicated above, by involving the institutions appearing as the result of content analysis. Considering that the focus of present blog entry is to present the research method it is relevant to briefly review the most important theoretical suggestions in that relation.

In our case the leaders of institutions and the main actors of the system appearing after the content analysis are considered as opinion leaders or influentials, who have direct impact and affection on their environment. Studying the literature we can conclude that opinion leaders can be characterized by high social activity and prestige (Weimann, 1994). These findings are coinciding with our intentions to interpret the child protection system in a new way, using factors resulting from the connection-network approach.

It is a well-known fact that everyone needs others to achieve one’s aims. We do not have to explain either how significant the interpersonal relations are because we spend our entire life in interactions with others, we live, study or work together. We know that humans are basically social beings (Gordon-Burch, 2007; Aronson, 2008). For several reasons, we may need the map of a group’s social links, in this case, that of the child protection system – in the current case, it’s necessary because those belonging to the given structure, the related individuals can access services that they could not as an individual (Coleman, 1990), so a truly functioning structure facilitates the access to social services, it distributes their scope. This map is called a sociogram and its method of creation is sociometry. According to Mérei, human relations, regardless of the content of their realization, are primarily emotional and are based on sympathy (Mérei, 2006). One of the corner stones of the theory is the assumption that these are identical with the spontaneous linkage driven by emotions and so with the system of networks formed between the given institutions – and of course between their employees – and lying in the background. This survey of social relations, the depiction of networks based on these responses and the interpretation of all these are jointly known as sociometry. Per the result of the sociometric examination, we can calculate several indicators, on the basis of which we can draw conclusions in relation to the given group.

Let us briefly review these indicators. The reciprocity index expresses the ratio of mutual relations within the group. The density index reflects the number of mutual relations per participant in the social field. The cohesion index helps us determine what percentage of the possible relations from a sociometric aspect was realized. The index of requited relations shows what percentage of the declared relations is mutual.

During the collection of data, we used a sociometric questionnaire of 18 questions because once we use the sociometric survey for research purposes, it is better to apply a choice of limited numbers. This is mainly justified by the later evaluation and calculation techniques. We have to emphasize that this examination method is not conducted in artificial scenarios. Since we examine a real, existing community, a dynamic and living network or system, the examination also takes place in real locales, at the location of the child protection system, in its real-world context.

The questionnaire, more precisely its questions were adjusted to the context as well, in order to achieve a higher level of involvement in relation to responders, thus increasing the reliability and validity of our results. Our questionnaire contained questions related to sympathy choices, trust, assertiveness, professional activity and professional competence.

Before we depict, introduce and analyze the network behind the child protection system, we have to mention, however, that this type of application of the method can be considered new, so it definitely has its limitations. Sociometry, as a method, is often used to reveal and analyze the internal structure of certain groups and not explicitly to discover the main intergroup connection points – in this case, the connection points identified between the participants of the local child protection system.

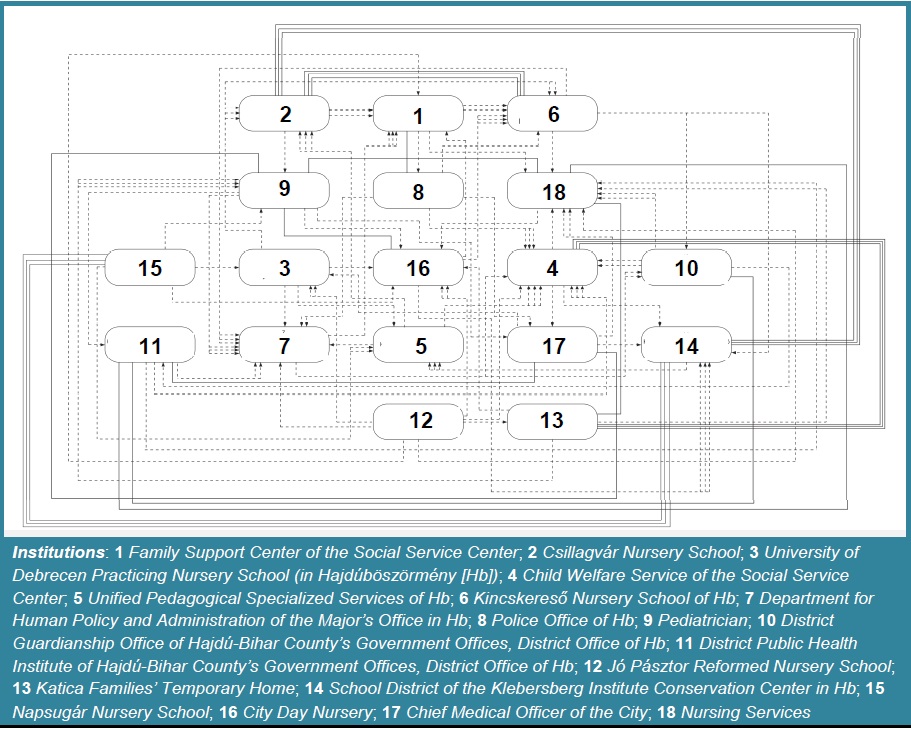

Figure 1.

The Sociogram of the Local Child Protection System

(Click on the image to enlarge it!)

By looking at the sociogram of institutions participating in the work of the child protection system, it immediately becomes obvious that we can talk about a relatively unified and coherent structure; the number of institutions situated at the periphery can be considered to be low. However, we can state that these institutions, fulfilling a less central role, are also connected to our system, therefore we can consider the flow of information to be ensured, while the distribution of resources being accomplished through these connections may be considered relatively balanced.

The central position of some institutions – such as the Child Welfare Service of the Social Service Center, the Family Support Center of the Social Service Center, and the Department for Human Policy and Administration of the Major’s Office in Hajdúböszörmény – is conspicuous. These institutions definitely play a significant central role in the system of child protection as the result of their function in public administration.

As we have mentioned before, we are able to visually depict not only the given system, the connection points between members of the system and the social-network structure during the sociometric analysis, but we can also calculate numerous indicators that help us draw valid conclusions regarding the system.

The mutual index of the child protection system of Hajdúböszörmény – namely, what percentage of the participants has a mutual relation – is 88%. In the case of a standard group with an appropriate social history, this value is usually between 85 and 90%. The density index, which expresses the number of mutual relations per participant within a system, had a value of 1.6 in our case. This value is above average since the standard value of this factor is between 0.9 – 1.1. After the analysis, we identified that the value of the cohesion index – with the help of which we can express what percentage of the relations, that are possible from a sociometric aspect, was established – was outstanding in relation to the local system of clearly child protection, since we consider 10-13% the standard value, while it was 27% in our case. The indicator of requited relations shows what percentage of the declared relations is mutual. The resulting value of 36% in our case is outside of the optimal zone, which falls between 50-60%. In relation to our system, this indicator may be less optimal because the legislative framework of the system certainly seems to define a type of hierarchy or path, or at least affects it.

By analyzing and interpreting the data, we can clearly state that the hidden and deep network, the existence of which we only assumed previously, indeed exists in the local child protection system. Although we have only examined the existence of this structure within the present blog entry, we can state that our structure complies with the main principles based on the logic of social-networking analysis.

References:

Aronson, E. (2008) The Social Being. Budapest: Közgazdasági és Jogi Könyvkiadó

Coleman, J. S. (1990) Foundations of Social Theory. Cambridge, M.A.: Harvard University Press

Ehmann, B. (2002) Deep in the Text – The Psychological Content Analysis. Budapest: Új Mandátum Kiadó

Gordon, T. & Noel, B. (2016) Human Relations. Budapest: Assertiv Kiadó

Krippendorf, K. (1999) Content Analysis. In: Sallay, H. (ed.): Collection of Methodological Texts. Debrecen: Kossuth Egyetemi Kiadó pp. 105-153.

Krippendorf, K. (2013) Content Analysis – An Introduction to Its Methodology. Sage Publications, Inc.

Mérei, F. (2006) The Hidden Network of Communities – The Sociometric Interpretation. Budapest: Osiris Kiadó

Weinmann, G. (1994) The Influentials. People Who Influence People. New York: State University of New York Press

The law of children’s protection and child welf administration, law XXXI. of 1997.

[1] The empirical study which is the bottom line of the present blog entry was conducted within the framework of the project Regulatory Tools for Local Public Services implemented by the „MTA–DE Public Service Research Group“ of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences and the Faculty of Law at the University of Debrecen. The results of the research see in the volume of Tamás M. Horváth and Ildikó Bartha (eds.)(2014) Rings and Avenues – How are services supplied by an average settlement in Hungary? Budapest-Pécs: Dialóg Campus,