Armenia is a country of long-standing traditions where prevalent social perceptions often associate women primarily with the private and family spheres thus limiting their opportunities for self-realization in public and political aspects of life. This note examines the main challenges and efforts have been made in the country to improve women’s political participation and representation in decision-making positions. Read more… (Liana Aghabekyan)

Armenia is a country of long-standing traditions where prevalent social perceptions often associate women primarily with the private and family spheres thus limiting their opportunities for self-realization in public and political aspects of life. This note examines the main challenges and efforts have been made in the country to improve women’s political participation and representation in decision-making positions. Read more… (Liana Aghabekyan)

by Liana Aghabekyan

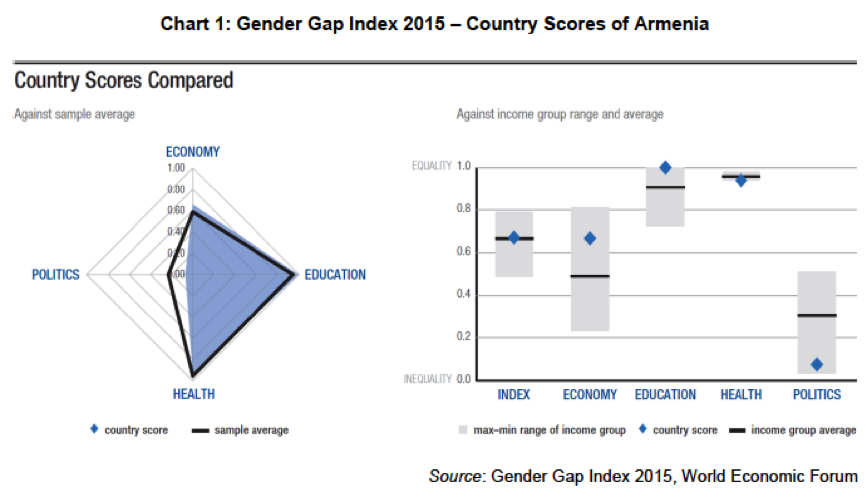

Armenia is a country of long-standing traditions where prevalent social perceptions often associate women primarily with the private and family spheres thus limiting their opportunities for self-realization in public and political aspects of life. Gender stereotypes are thought to contribute to women’s lower levels of representation in politics, formal employment and as business leaders. Stereotypes can also have a negative impact on men, especially those that portray men as solely responsible for providing financially for their families. According to a recent survey by Yerevan State University centre for gender and leadership studies 60 per cent of Armenians agree that there is “inequality among men and women in Armenian society,” and only eight per cent disagree with this statement. Annual assessments of the extent to which men and women are equal in Armenia, compared with other countries of the South Caucasus, indicate that Armenia falls behind its two neighbours in ranking. The 2015 Gender Gap Index ranks the country 105 out of 145 countries. Although the country scores relatively high in terms of equal access to education, these scores are counterbalanced in terms of economy, politics and health issues.

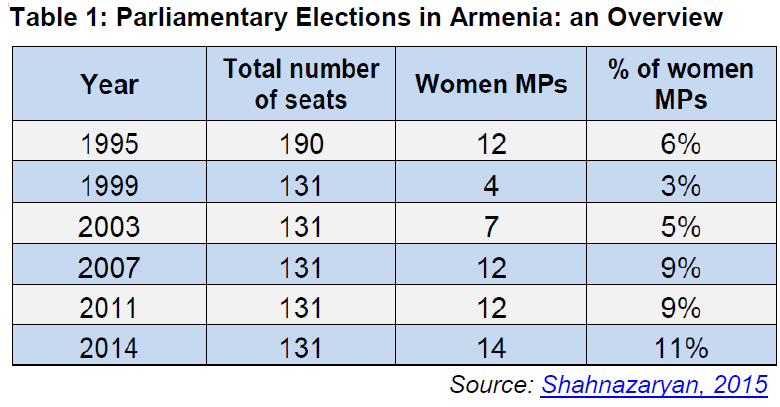

Although women in Armenia comprise more than half of the population with higher and postgraduate education, their political participation and representation in decision-making positions remains critically low. Despite efforts to use positive discrimination (a quota system) to assist women to enter politics, women’s low level of representation in national government has shown minimal change over time. At present, women comprise less than 11 per cent of parliamentary deputies, despite of the 20 per cent minimum quota in party electoral lists as stipulated by the Electoral Code of the Republic of Armenia.Although women are much better represented in supporting and non-management positions, their limited presence in decision-making roles both at national government and local level means that women may not be adequately involved in policy making about critical development issues. Women are also under-represented in regional and municipal administrative bodies that set priorities locally. Currently there are no women at regional high-level authorities (governors). At the local level, women comprise just over nine per cent of community councils. Out of 866 rural communities, only 18 are led by women (around two per cent). At the municipal level, 49 cities, including Yerevan, have never had women mayors. Notably, these institutions may lack the capacity to adequately serve their female constituents. Moreover the country is undergoing consolidation reforms which means that small municipalities are being merged with neighbouring ones to ensure provision of higher level of public services to the citizens. However, based on the results of first local elections in consolidated municipalities, this reform seems to create additional challenges for women.

Recently in 2016, in order to address some of the abovementioned challenges and comparatively just the unequal reality the governmentincreased the previously used 20% gender quotas accordingly to 25% for 2017 and 30% for 2022. Parliamentary elections requiring political parties to apply quotas in each group of 4 candidates starting from the first number in the list instead of previously used second (see Art. 83(4) and 144(14) of the Electoral Code). It will also assure that each party has at least one representative of underrepresented gender. Similar provisions will apply for Local Councils’ elections in three biggest cities in the country, namely Yerevan, Gyumri and Vanadzor. However, there is a risk that the changes may have a limited impact given the introduction of district lists/open lists, where no gender requirements apply and which, again, may become an additional challenge for local women to get elected as local self-government authorities (head of community or a member of community council).

is a risk that the changes may have a limited impact given the introduction of district lists/open lists, where no gender requirements apply and which, again, may become an additional challenge for local women to get elected as local self-government authorities (head of community or a member of community council).

To fill the gaps the top-down approach leaves, a bottom-up method is used in some of the regions throughout the country to develop a pool of qualified, educated, informed and active women citizens interested either in socio-economic or public and political participation. Particularly grassroots level local organizations called “Women’s resource centers” (WRC) have been created in Syunik, VayotsDzor and Tavush regions, which work actively towards women economic, social and political empowerment in the respective areas. Handicrafts development has been selected in Syunik region as the most relevant mean for giving local women the opportunity to earn some income, while at the same staying at home to take care of households. The experience shows that this rather simple way of earning helped women to gain self-confidence, feel themselves important for society and become good examples for their children. Moreover, the example of this project reveals a strong interconnection between economic and political empowerment. The women who get trained, enhance their skills and feel capable of supporting their families financially increasingly become interested in local politics. This was evidenced in 2012–2013, when WRC’stargeted work towards women political empowerment on the eve of local self-government elections resulted in 70% election of women candidates and therefore significant increase in women’s representation in Syunik region and VayotsDzor regions.

Armenia is currently on the eve of elections cycle again. Upcoming local self-government elections in fall of 2016 and Parliamentary elections in spring of 2017 awake the hope to believe that the combination of abovementioned top-down and bottom-up approaches will bring us a step closer to women’s equal representation in decision-making bodies. And the importance of equal representation does not solely lay in “women’s rights” issues, or in “utilisation of the potential of half of the country’s population” but in resulting a more just, fair and democratic society considering the needs, constraints and opportunities of its each member.