Discussions on the possibility to attribute liability to legal persons for committing offences are far from new. The Romans already had a clear position on this and were opposed to the idea that a persona could be anything else than a natural person. Thus, Ulpian specifies that a municipium cannot be responsible for dolus since it is a legal person, i.e. a fictive entity (Catargiu, 2013, 26.). Even though this default position evolved and despite the consequent lenience towards accepting forms of liability (including criminal liability) of legal persons, the classical idea that legal persons could not be criminally punished prevailed for a long time – and resulted in the adage ’societas delinquere non potest’. Read more… (Petra Ágnes Kanyuk)

Discussions on the possibility to attribute liability to legal persons for committing offences are far from new. The Romans already had a clear position on this and were opposed to the idea that a persona could be anything else than a natural person. Thus, Ulpian specifies that a municipium cannot be responsible for dolus since it is a legal person, i.e. a fictive entity (Catargiu, 2013, 26.). Even though this default position evolved and despite the consequent lenience towards accepting forms of liability (including criminal liability) of legal persons, the classical idea that legal persons could not be criminally punished prevailed for a long time – and resulted in the adage ’societas delinquere non potest’. Read more… (Petra Ágnes Kanyuk)

Discussions on the possibility to attribute liability to legal persons for committing offences are far from new. The Romans already had a clear position on this and were opposed to the idea that a persona could be anything else than a natural person. Thus, Ulpian specifies that a municipium cannot be responsible for dolus since it is a legal person, i.e. a fictive entity (Catargiu, 2013, 26.). Even though this default position evolved and despite the consequent lenience towards accepting forms of liability (including criminal liability) of legal persons, the classical idea that legal persons could not be criminally punished prevailed for a long time – and resulted in the adage ’societas delinquere non potest’.

Discussions on the possibility to attribute liability to legal persons for committing offences are far from new. The Romans already had a clear position on this and were opposed to the idea that a persona could be anything else than a natural person. Thus, Ulpian specifies that a municipium cannot be responsible for dolus since it is a legal person, i.e. a fictive entity (Catargiu, 2013, 26.). Even though this default position evolved and despite the consequent lenience towards accepting forms of liability (including criminal liability) of legal persons, the classical idea that legal persons could not be criminally punished prevailed for a long time – and resulted in the adage ’societas delinquere non potest’.

The Brief Evolution of Criminal Liability of Legal Persons

Even though during the Middle Ages the concept remained somewhat controversial, the balance shifted in favour of accepting criminal liability of legal persons. However, this evolution was inhibited in the aftermath of the French Revolution. It was not until 1992 that the French Criminal Code officially reinstalled the criminal liability of legal persons. As to the former Soviet republics and Soviet satellite states, the State did not feel it necessary to install such criminal liability, considering that all undertakings were owned by the state and the autonomous powers of the managers were thus very limited. By contrast, the climate in the Anglo-Saxon countries provided incentives to recognize the legal persons’ criminal liability (see Stanila, 2014, 111–113.).

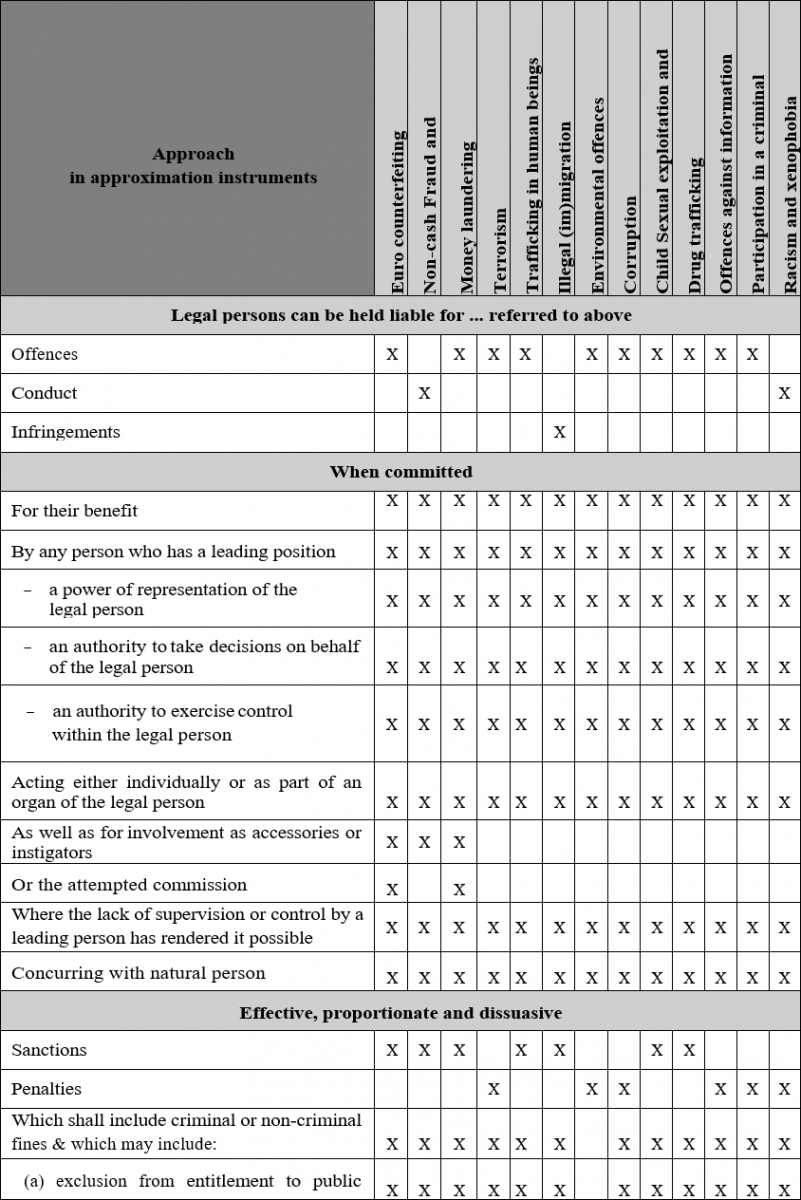

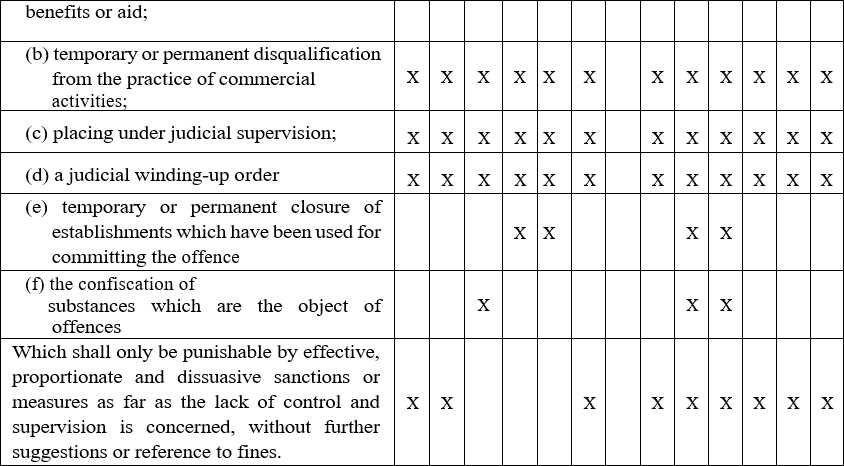

As a result, in today’s European Union, the landscape is scattered. The EU requires the Member States to ensure the possibility of sanctioning legal persons involved in crimes. Many EU legal sources (directives and council framework) contains the criminal liability of legal persons with very similar regulations. The regulated crime types are such as Counterfeiting; Fraud and counterfeiting non-cash means of payment; Environmental offenses etc. (Sántha, 2017, 184–186.). The following table provides an overview of the legal person-related provisions in the approximation instruments (Vermeulen & Bondt & Ryckman, 2012, 95–97.):

The Main Motives of the Establishment of the Criminal Liability of Legal Persons

Criminal Liability of Legal Persons Under the Hungarian Regulation

As early as during the accession negotiations, the EU specified it as a ‘top priority’ that the legal instrument of criminal liability of legal persons was integrated by Hungary into its legal system (Fantoly, 2008, 21.). Therefore, compliance with the legal harmonisation task related to our EU membership required the criminalisation of the conducts of legal persons to be established, which broke the exclusive enforcement of the principle of culpability in Hungary – which is incorporated in our criminal law on the level of principles – meaning that a person may be criminally liable only for punishable conduct committed guiltily. However, it shall be noted that there were other motives as well; the regime change which occurred in Hungary in 1989, the transformation of the economy and the law accordingly, as well as the emergence of the legal person ‘as new legal instrument’ already foresaw the kind of necessity that the creation of the criminal liability of legal persons shall be considered (Polt, 1989, 324–335.). The change is illustrated by the fact that in 1990, 19,401 companies with legal personality operated in Hungary, and by 1994, the number of these companies exceeded 94,000 and exceeded 214,000 by 2004.

The Hungarian Solution – and the Principle of Culpability

Although the Criminal Code (Act C of 2012) did not define the concept of culpability, legal literature did develop the fundamental definition thereof. Accordingly, culpability is the current, attributable psychical relation between the perpetrator and the conduct committed, which prevails at the time of the conduct being committed (Horváth, 2012, 136.). However, the forms of culpability are specified by the Criminal Code itself, which are none other than intent and negligence: A criminal offence is committed with ‘intent’ if the person conceives a plan to achieve a certain result, or acquiesces to the consequences of his conduct. (CC Section 8.); ‘Negligence’ means when a criminal offence is committed where the perpetrator is able to anticipate the possible consequences of his conduct, but carelessly relies on their non-occurrence, or fails to foresee such possible consequences through conduct characterized by carelessness and neglectfulness. (CC Section 7.). Accordingly, criminal liability may be established exclusively for conduct committed intentionally or with negligence: ‘Criminal offence’ means any conduct that is committed intentionally or – if negligence also carries a punishment – with negligence, and that is considered potentially harmful to society and that is punishable under this Act. (CC Section 4 (1))

The strict dogmatic rules which pervade the entire Hungarian criminal law did not allow for the rules of criminal liability of legal persons to be included in the Criminal Code, considering the strict principle of culpability. Therefore Hungary chose the solution that a separate act – namely Act CIV of 2001 on Criminal Sanctions in Connection with the Criminal Liability of Legal Persons (hereinafter: Legal Person Act) which entered into force on 1 May 2004, when Hungary joined the EU – regulates the terms and conditions of criminal liability of legal persons, as well as the related procedural rules. The rules related to the system of sanctions of the effective Criminal Code include only a reference to that measures to be imposed on legal persons are regulated by a separate act (CC 63 Section (1) point i)). In addition, we have to emphasise that the Hungarian criminal law system of sanctions is dual, which means that it applies penalties and measures. Imposing any penalties requires culpability in all cases, therefore the legislator deemed that exclusively measures could be applied against legal persons.

General Provisions

According to Professor Tóth, there are three forms of the criminal liability of legal persons – which can be combined – in the practice in general: the so called ‘objective liability’ of the organisation – this is also called result liability –; when the leader of the organisations takes responsibility; and when the collective leadership will be held liable for the crime committed with the legal person. Hungarian criminal law mostly follows the third option (Tóth, 2015, 368.).

In order to impose criminal sanctions on the legal person, the Legal Person Act requires that first the criminal liability of the natural person acting on behalf or in the interest of the legal person is established (exceptions to this rule are possible only in the cases specified by law, see Legal Person Act Section 3 (2)) and therefore – indirectly – the liability of the natural person constitutes the basis for imposing criminal sanctions on the legal person (Sántha, 2002, 91–92.). The natural person acting on behalf or in the interest of the legal person who commits the criminal offence intentionally while seeking or aiming for profits for the legal person may be the executive officer, member or employee of the legal person – in the latter case only if the omission of the executive officer can be established, i.e. the fulfilment of the controlling obligation could have prevented the criminal offence –, or may also be anybody, if the criminal offence results in profits for the legal person, or if the criminal offence is committed with the use of the legal person and the executive officer of the legal person is aware of the committing of the criminal offence. If the liability of such a person is established or is granted a conditional sentence by the court, or if the court issues a warning, then measures may be applied against the legal person.

Possible Measures

The Hungarian criminal law allows three measures to be imposed on legal persons: winding up the legal person, limiting its activity and imposing a fine (Legal Person Act Section 3 (1)). Winding up the legal person – as the strictest sanction – may be applied only if the legal person is not pursuing any lawful economic activity and if the legal person had been formed for the purpose of concealing crimes, or if the actual activity of the legal person is designated to conceal crimes (Legal Person Act Section 4 (1)).

The Hungarian criminal law allows three measures to be imposed on legal persons: winding up the legal person, limiting its activity and imposing a fine (Legal Person Act Section 3 (1)). Winding up the legal person – as the strictest sanction – may be applied only if the legal person is not pursuing any lawful economic activity and if the legal person had been formed for the purpose of concealing crimes, or if the actual activity of the legal person is designated to conceal crimes (Legal Person Act Section 4 (1)).

The court may limit the activity of the legal person between one to three years. The act lists the rules related to the restriction of the scope of activity only in a non-exhaustive manner, therefore any restriction that the court deems appropriate may be ordered. The restrictions listed by the Legal Person Act includes restrictions such as not being allowed to participate in public procurement procedures, conclude concession contracts, pursue activity for public benefit, etc. (Legal Person Act Section 5 (2)).

The maximum amount of the fine is triple the value of the financial gain or advantage achieved or intended to be achieved through the criminal offences, but at least five hundred thousand Hungarian Forints. The value of the financial gain or advantage may be established by the court through estimation in a case where the value of the financial gain or advantage achieved or intended to be achieved cannot be established or can be established only through unreasonable efforts. If the financial gain or advantage achieved or intended to be achieved is not of financial nature, then the fine will be determined by the court taking into consideration the financial situation of the legal person (Legal Person Act Section 6).

As it was highlighted – and also summed up – by Dávid Tóth, one of the most famous of the few Hungarian cases was the Szegedi Paprika case. The main actors of the case were the Szegedi Paprika firm and the Kotányi GmBH firm which were in a business relationship. The latter bought from the Szegedi Paprika firm 20 ton of spicy pepper (paprika) in 2004 which contained more than 5 micrograms per kilogram aflatoxin (a poisonous carcinogen that is produced by certain molds). This number exceeded the permissible level and can be harmful to humans when it is consumed. The Kotányi GmBH notified Szegedi Paprika about this and its assistant transmitted this to the Quality Control Department who confirmed this claim and reported to the company leaders as well. They bought back the 20 tons of spicy pepper and after that, they sold more than 3.5 tons of these as a gourmet meal. They also sold the other parts of the paprika as so-called ‘diluted meal’. The accused natural persons, the leaders of the Szegedi Paprika firm decided over the resale of the spicy pepper – with this decision they put goods harmful to human health back on the market. The firm also gave deceptive information about the origin of the spicy pepper and they were not allowed to use the label ‘Szegedi’ which means from the Hungarian city of Szeged since most of the spicy pepper was from Spain, it was solely an imported good. The accused natural persons were convicted of misuse of harmful consumer goods – a crime which can be accomplished when a person who prepares or possesses any consumer goods for the purpose of distribution that is harmful to health – and punished with a fine and the legal person was also fined for 15 million Forints by the Szeged Regional Court. The second instance court increased the sanctions due to the dangerous nature of the crime and the personal circumstances of the accused (see Tóth, 2019, 186–187.).

Unfortunately, we have to say that compared to the original rules, the Legal Person Act, which was amended several times, still to this day fails to fulfil its purpose in Hungary. In judicial practice, the number of criminal convictions of legal persons is very low and almost close to non-existent statistically (Tóth, 2019, 185–186.). This may be owed also to the fact that the Legal Person Act ensures opportunity for criminal accountability only in case of conduct committed with intent, however, practice shows that in case of criminal offences committed in the interest of legal persons the typical form of culpability is negligence (Sántha, 2012, 543.).

For a list of references, click HERE.

Author: dr. Petra Ágnes Kanyuk

Ph.D. Student at the Géza Marton Doctoral School of Legal Studies of the University of Debrecen, Department of Criminal Law and Criminology

The study was prepared with the professional support by the Research Scholarship for Ph.D. Students No. ÚNKP-19-3, granted by the Ministry for Innovation and Technology in the framework of the New National Excellence Programme.